Olding ward, London Chest Hospital, c.1925. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/2/7

London Chest Hospital was founded in 1848 by a group of philanthropic bankers and City merchants, many of whom were Quakers, who had witnessed the success of the Brompton Hospital and wished to provide the same service to residents of the City and the East End of London. As a general hospital, The London Hospital was unable to provide specialist care to chest patients, and the other London chest hospitals were too small or too far away to provide services to patients in the east of London.

Initially opening as a public dispensary based in Liverpool Street, it proved an immediate success and limits soon needed to be placed on the numbers of patients treated. Funds were soon raised to build a hospital, and the site next to Victoria Park was purchased as it had extensive grounds so that the hospital could start small and expand.

Postcard showing patients sitting in deck chairs on the front lawn of the hospital, 1923. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/1/4

Amongst the proposed designs for the hospital was a ‘Crystal Sanatorium’ presented by Sir Joseph Paxton, designer of the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition. The Illustrated London News described the principles of the building, “in which the purity of the atmosphere should be secured by a process of artificial filtration and an equable and pure temperature… the outer air being admitted by tunnels to the centre of the building”. However, this idea was too expensive to put to use, and instead of a Crystal Sanatorium, the residents of Bethnal Green had to make do with a typical Victorian hospital. (RLHLC/X/17)

Prince Albert laid the foundation stone for the hospital in 1851, and an initial sum of £30,000 was raised to build the hospital. In 1853 the hospital opened with 12 beds, expanding to 80 by the end of the decade. It was a huge success, and by 1862 had treated 9074 out-patients and 442 in-patients. Two further wings were added in 1865 and 1871, providing 160 beds in total.

From the beginning, the mission of the hospital was to treat patients with all chest conditions, not just tuberculosis. No more than half of the beds were to go to tuberculous patients; however, this requirement was relaxed by 1864, as the majority of cases were tuberculous. As you can see from this table, this was still the case in 1924, a year after the hospital clarified with a change of name that it was “The City of London Hospital for Diseases of the Heart and Lungs”.

1924 Inpatients: (All diseases with more than 10 admissions) 315 Pulmonary tuberculosis* 43 *PT and other complication 29 observed for PT, found to have no disease 35 Fibrosis of Lung 30 Bronchitis and Emphysema 29 Mitral Disease 27 Pleurisy, Acute Serous 26 Bronchiectasis 25 Acute Lobar Pneumonia 24 Hypertrophy of Tonsils and Adenoids 19 Auricular Fibrillation 16 Asthma 15 Acute Bronchitis 14 Tuberculous Adenitis, Mediastinal 11 Acute Lobular Pneumonia 11 Acute Tonsilitis

Female patients on the balcony taking air, 1923. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/2/4

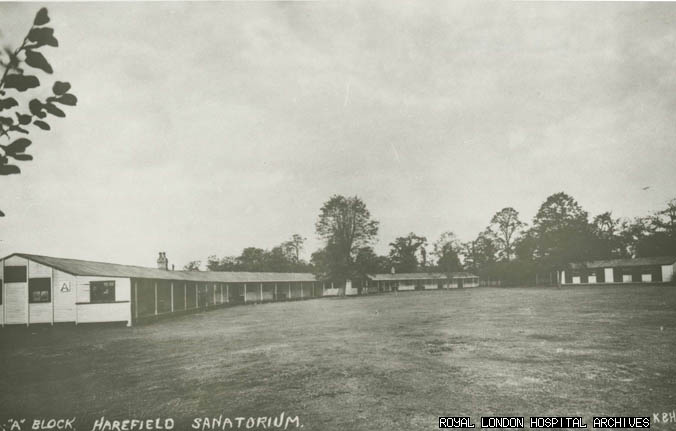

Nineteenth century principles of tuberculosis treatment were very different to the later methods that would develop in the sanatoria, and hot, airless wards were the order of the day. Unlike the open shapes of later sanatoria, such as Frimley or Harefield, the London Chest Hospital was built in a standard shape, lacking balconies. As the new ideals took hold, in 1900 two balconies were added. Each could take 8 patients, who remained on balconies day and night regardless of weather; beds were fitted with Mackintoshes to keep patients dry in the rain!

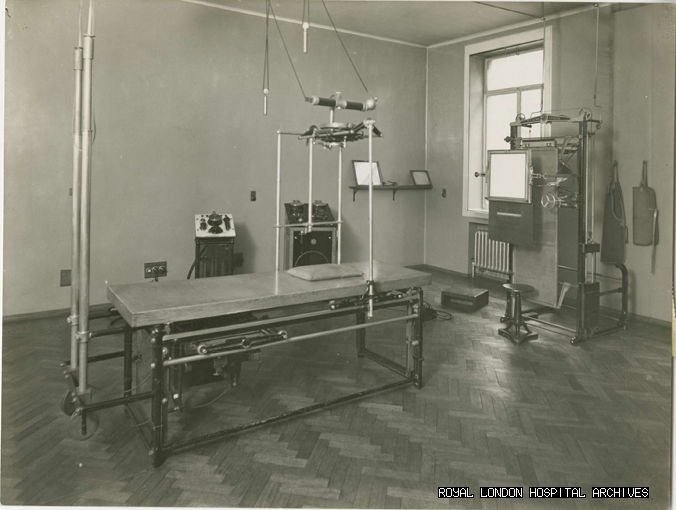

As the twentieth century progressed, the hospital added as dispensary, providing outpatient care to patients in Bethnal Green and Hackney. The hospital maintained a sanatorium, initially in Saunderton, Bucks, then in Camberley, and later in Arlesey. The 1920s brought a new X-ray department, creating about 1000 plates a year in 1925. The surgical ward was out-of-date and unable to meet demands by 1913 – the intervening war delayed improvement, but a new surgical wing was opened in the 1930s as a result of a public appeal. A clinic for breathing exercises was established in 1939, and a physiotherapist specialising in thoracic work was appointed in 1944 .

X-ray Examination Room at the London Chest Hospital, C20th. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/5/1

The hospital was funded by the typical subscription model; unusually, however, local workmen started to club together, contributing a penny each from their weekly wages. These societies frequently donated over £1000 per year, a considerable sum which enabled them to recommend patients. This shows the strength of support the hospital enjoyed from the local community, but also suggests that the patients’ realised that the expense would be too much to bear individually. Appeals were another key feature of the hospital’s fundraising efforts, with adverts appearing on buses and in the press, as well as spoken appeals on the BBC.

Continued growth saw more than 40,000 outpatients treated per year by 1939. During World War II, The London Chest Hospital became an EMS hospital, with a minimum of 75 beds reserved for air raid casualties.

Bomb damage to the exterior front facade of the Hospital, 1941. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/8/1

Medical staff wheeling objects salvaged from the rubble across the bomb site, 1941. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/8/16

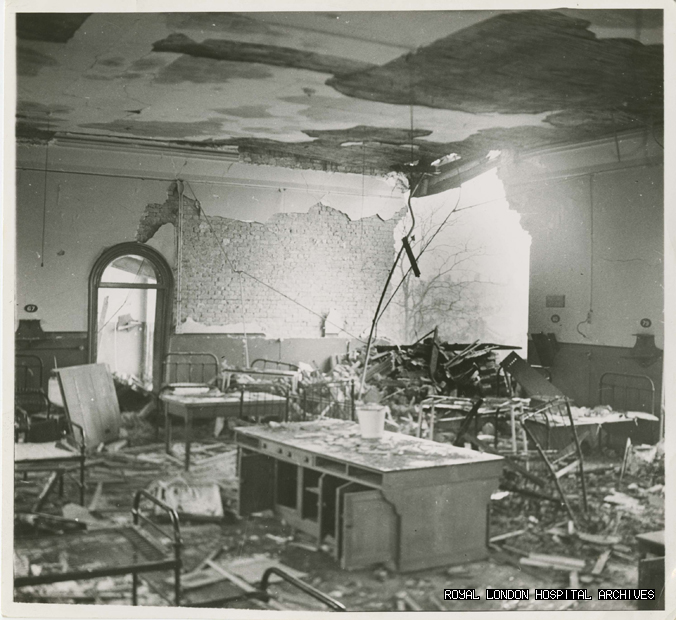

Bomb damage in a ward in the North wing, 1941. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/8/27

The minutes of the Committee of Management tell the next part of the hospital’s story:

28 March 1941: The Secretary reported that on the night of March 19th the Hospital buildings suffered severe damage through enemy action, the Pathological Laboratory and Chapel being completely demolished, one section of the Nurses’ Home destroyed, the North Wing of the hospital so severely damaged that it will have to be taken down as a dangerous structure, and the roof of the South Wing completely gutted by fire from incendiary bombs.

There were in the Hospital at the time 85 patients and approximately 60 staff.

There were no deaths and the staff in spite of injuries from broken glass etc. in a very short time removed the patients to safety in the Parmiters School nearby. Five nurses were buried in the debris of the Nurses’ Home and were rescued, having sustained only minor injuries.

The Vice-Chairman reported that members of the House Committee and Medical Staff attended the hospital the following morning and at an Emergency Meeting instructed the Secretary to endeavour to re-establish as soon as possible in some portion of the Hospital the Out-Patient Department, First Aid Post and Special Clinics.

The quest to re-establish the hospital suffered a setback in May, as the hospital was bombed again and all the repair work was destroyed. However, the Outpatient Department, and clinics such as the Tuberculosis Dispensary, were back at work soon after the bombing, and other patients were sent to the county branch at Camberley while re-building took place. By October patients were back at the hospital, where some rearrangement had taken place; wards now occupied the ground and first-floors, and first-floor patients were moved into the basement each evening. Surgery was slower to re-establish, although minor surgery was allowed by 1943.

The minutes also reveal some of the measures taken to prevent the spread of tuberculosis within the hospital. They were not always successful, as in 1946 some nurses were found to have contracted the disease, but there was no systemic reason found to explain why this occurred. Tuberculosis patients were kept to their own wards, with no shared corridors with other patients. Medical staff were x-rayed on arrival at the hospital, and routinely re-scanned every 1-6 months depending on their Mantoux status (which would indicate if they had been exposed to tuberculin). Nurses, particularly from rural Ireland or Wales, who were shown not to have been exposed to tuberculosis were also not allowed to work on the tuberculosis wards.

In 1948, as part of the creation of the NHS and the abolition of Voluntary Hospitals, London Chest Hospital amalgamated with Brompton Hospital for the purposes of being designated a Teaching Hospital. As the century progressed, and the need for tuberculosis treatment lessened, the hospital expanded its focus on other diseases of the chest, such as cardiology. Brompton and The London Chest Hospital worked together until the 1990s, when the London Chest Hospital was aligned instead with the Royal London Hospital, located in nearby Whitechapel. In April 2015, services from the London Chest Hospital moved to St Bartholomew’s Hospital (Barts), within the same administration group, and the building was sold.

Female patients taking the air on the cleared site of the ground floor of the North Wing, London Chest Hospital, c. 1948. Caption “But for an air raid these patients at the London Chest Hospital might have been three storeys up. As it is they are taking the air on the ground floor on the cleared site of the North Wing that was destroyed in 1941. ” New York Times Photos, 2, Salisbury Sq., Fleet Street. Photograph: Royal London Hospital Archives. RLHLC/P/2/2/12

Sources:

RLHLC/X – Miscellaneous Records

RLHLC/A/2 – Minutes of the Committee of Management